September 11thIn 1967 my father returned to Barrow at the age of 18 after spending four years at a boarding school in Sitka, Alaska and subsequent job training in Oregon and California. Some Native youth were sent to away boarding schools while in elementary school, often hundreds or sometimes thousands of miles away from their homes. Many young Inupiaq men and women from Northern Alaska attended Mount Edgecumbe in Sitka, about 1,000 miles away from Barrow; others attended Wrangell Institute 1,200 miles away from home in southeast Alaska, St. Mary’s, Copper Center in southeastern interior Alaska, and Chemawa in Oregon, amongst others. After graduating from these Native boarding schools, many were then sent to trade schools in the Lower-48 states. My father arrived back in Barrow in time for the spring whaling season in 1967, and afterwards was sent out with a group of Barrow men to Yahachts and Portland, Oregon for a job core and another program sponsored by the Borough of Indian Affairs. The year my father returned to Barrow was an important time within the realms of governance and Northern history because the Alaska Native land claims negotiations were underway, and Inupiat people fought for hunting rights and the establishment of local schools to keep the youth closer to home. The largest on-land oil discovery in North America was occurring, which would bring more changes to the Inupiaq homeland and lifestyle. The Inupiat towns of Northern Alaska were being further developed. Throughout times of great change, whaling continued to be a catalyst that brought the Inupiat community closer together. The whole community participated and was needed to harvest a whale, while the whale meat provided food for most everyone, not just the crews.

Within whaling, young men (and women too) show their respect and earn respect from the captain and crew like everyone else- it might take a few seasons, but they earn their way by starting with the jobs of chipping ice, breaking trail and preparing everything for the crewmembers. My father, like other Inupiat men of his age who had just recently returned to their northern communities, were handed tasks such as breaking a trail for the crew to utilize once the bowheads began migrating through the open leads. When breaking trail, they first scout the ice conditions to decide the placement of the route, which depends upon the ocean current, the wind, and the direction the ice is moving. Using different types of ice picks, they blaze the jagged pieces of ice that protrude through the shorefast ice for a couple of miles until they reach the open lead. This is done so the snowmachines and skin boats are not damaged when the crew makes their way out to the camp. Meanwhile, other family members gather materials like sleeping bags, skins, plywood, tents, and everything else needed for whaling. Many able-bodied people are needed for the jobs done during the months leading up to the spring whaling season. Usually men head out the previous summer and fall to hunt for seals, while the women work on sewing skins together with special water-proof stitches to make covers for the boats. These sealskin boats are still used today because they are much quieter when launched and are more efficient when chasing a whale. Women also sew the qatiginisis (the white covers that are used to help the whalers parkas blend in with the snow on the ice), while many other jobs are done in preparation of the spring whaling season. Inupiat youth who had been away for years at such young ages were now returning to a whaling community. In 1971, the U.S. Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and the people of the North Slope formed the Native-owned corporation known as the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC). Wages then went up from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) pay rate of $3.50 per hour to a starting rate of $6-7 per hour for the ASRC jobs. In attempting to understand and describe the history of boarding schools and spring whaling events, I wish I could say that I understand my father and the feelings that resonated in the air of 1967 Barrow a bit better. I can only draw from facts I’ve been told and the experiences I’ve had. Albeit Inupiat youth from that generation (or two, three or even more generations back) experienced being away from home for years at a time at much younger ages, I can understand what it now feels like to be gone for so long and to return to a community of what I call home, especially after spending more than six years away at school.

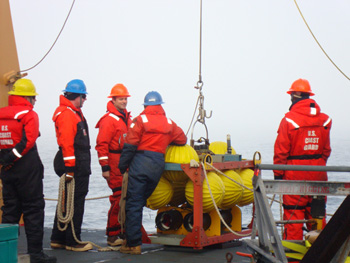

At 11:30 am Josh Jones, a marine mammal technician from the University of California San Diego and part of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, deployed his first HARP instrument of the trip in the Chukchi Sea, a joyous occasion. HARP stands for Hull And Riser/mooring Program. Josh’s same HARP instrument was recovered from the bottom of the ocean floor yesterday, refurbished with new hard drives and batteries, and redeployed. Over the next year, this instrument will sit on the ocean floor roughly 250m below the surface. The instrument takes intermittent points of measurements, casting a floating buoy to the surface everyday at midnight in order to conserve energy in its battery-powered motor. The major objective of Josh’s study is to monitor the mammals that migrate or forage near the coastal regions of Barrow, which was originally funded through the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. The natural noises picked up on Josh’s instrument include bowhead whales, belugas, ringed seals, bearded, walrus and ice freeze-up and break-up as well. Man-made noises include seismic surveys and shipping (boats, icebreakers) activities. One major concern of the area is how the behaviors of migrating and foraging mammals will change with a potentially ice-free Arctic environment. Some scientists predict this will happen in about 2030, so this recovered data will help form a baseline of knowledge for future scientific studies on animal acoustics in this area. The behaviors of many mammals evolve around the existence of ice in these areas. Many of the mammals mentioned above are bottom-feeders and depend on the ice as a platform for diving to relatively shallow depths to feed. When the ice moves, ideally so do the animals. When there’s no ice, there are no animals. Josh’s baseline of scientific knowledge helps to set a precedent for future comparative studies. After the deployment of Josh’s first HARP, people cheered him and the team of technicians and scientists who performed the work. When I asked how he felt, he offered a humble response about the ‘teamwork’ that goes into the entire process of deploying and recovering HARP’s. While this is only a single instrument at one location in the Arctic, it will help form the larger baseline of scientific knowledge necessary to understand high-latitude climate change. A job well done.

Last updated: September 29, 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||||||||||