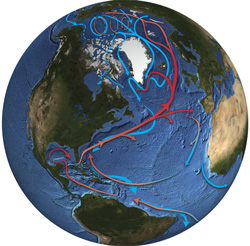

September 8thDr. Bob is a physical oceanographer. They seek to understand how oceans work. Other kinds of oceanographers address the subject in different ways. Chemical oceanographers study the content and chemical make up of the water. Geologic oceanographers are interested in ocean bottoms, while biological oceanographers, or marine biologists, study the creatures that live in the ocean. Physical oceanographers are interested in the water itself and how it moves. But Dr. Bob is a particular sort of physical oceanographer (“fizzo,” in the slang). Dr. Bob is the guy who actually goes to sea to collect the ocean measurements, the raw data. That makes him an “observational fizzo.” It’s a strange idea at first blush, studying ocean water. What’s to study? It’s wet, sometimes it’s rough, other times it’s calm and clear, good for snorkeling. Indeed, most people, when they look out over the ocean, seeing only the surface, think of the rest of the ocean as a great pool of undifferentiated water randomly sloshing around. We hope in the days to come to demonstrate that: 1) Not all ocean water is created equal. In some places it’s cold and in others it’s warm. Some ocean water is saltier than other water. And that difference in those seemingly mundane qualities, a pinch of salt here, a few degrees difference in temperature there, can determine the climate on land. 2) The ocean is constantly on the move both on the surface and in the abyss, and that, by moving, it performs magnificent, global-wide feats. 3) There’s one other thing, speaking for myself, I’d like to demonstrate by implication—that the ocean and its works are thrillingly beautiful, you won’t need to be a scientist to appreciate that. All you have to do is use your imagination to visualize vast quantities of water perpetually circulating out there beyond the horizon and all around the globe. Ocean Motion You can observe a couple features of ocean motion, waves and tides, from under a beach umbrella. Waves are caused by wind. The stronger the wind, the larger the waves, and when the wind drops, the waves relax. As kids we discovered tides when incoming water dissolved our sandcastles. Tides are driven primarily by the gravitational attraction of the sun and moon, but actually all other celestial bodies in the universe participate in tide formation. And since astronomers know precisely the position of all celestial bodies relative to Earth, tides in all oceans and seas can be predicted with a high degree of accuracy. When the moon is full and when it’s new, the high tide is higher and the low lower than during other phases of the moon. “I’m in the Arctic aboard the Healy doing what I love best. I couldn’t be better.” But there’s another kind of movement in the ocean, in all oceans, happening on such a vast scale they cannot be observed from shore or even appreciably from a ship at sea. They’re called ocean currents. That’s both a descriptive and a technical term. Let’s use this definition: An ocean current is a large quantity of water moving in a single direction. Their speed and direction will jink and waver in the short term, but in the mean they maintain that single direction of flow. The Gulf Stream is the best known of all ocean currents, but there are many others. Some are warm like the Gulf Stream; some like the Humboldt and California currents are cold. Some ocean currents flow north and south, others east and west. Flowing, they transport enormous quantities of heat from where there is too much—the tropics—to where there is too little—the Arctic. By doing so, they moderate climatic extremes on a global scale. Consider these two examples of ocean currents’ influence and power: San Francisco is damp and chilly in summer, while it’s hot and dry only a few miles inland, because the California Current flowing down from the north is cold. The wind, the ocean’s kindred fluid, blowing from the west, carries the chill into San Francisco Bay. The opposite obtains in England. By geographic rights, England should be frozen in winter. But instead its climate is moderate, because an offshoot of the warm, moist Gulf Stream flows past the British Isles. And that same west wind transports warmth onto England’s grateful shores. So let’s pause here with this brief introduction to fizzo, now that we can visualize these currents coursing like giant blood vessels through the body of the ocean. We’ll return to the subject another day with the aim of narrowing our focus on the specific current Dr. Bob is out here to study. But let’s add one more critical fact about ocean currents: All those currents coursing through all oceans of the world—they’re all connected one to the other in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans, in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, and in the Arctic Ocean. As far as oceanographers and mariners are concerned, there are multiple oceans and seas. As far as nature is concerned, there is only on single World Ocean. * * * Buying a cup of coffee in the ship’s store this morning, I ran into Josh, who’s recording whale and other marine mammal sounds with hydrophones attached to moorings that have been in the water for the last year, and asked him, “How’s it going?” “I’m in the Arctic aboard the Healy doing what I love best. I couldn’t be better.” In that we have one of the true joys of life aboard research vessels—the people. All of our people are excited and enthusiastic about their work delighted to be doing it in the Arctic. You can hear the enthusiasm in their voices and see the excitement in their eyes. What could be better than that, and the Arctic, too? Last updated: September 28, 2010 | |||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||