September 12thThe first thing one notices about the icebreaker Healy is her size. She is BIG. She’s the largest vessel in the Coast Guard. There are two other icebreakers in the fleet, Polar Star and Polar Sea, but they are one foot shorter than Healy with her length overall of 420 feet. She is a capable icebreaker, able to operate in 50 degrees F. below zero, to power through 4.5 feet of sea ice at three knots and through eight feet of ice by backing and ramming. But her primary mission is as a high-latitude scientific research vessel, and that makes her unique among Coast Guard vessels. (By the way, any vessel over 65’ in length is designated a cutter; anything shorter is a boat.)

It’s no small thing to adapt a vessel as a research platform. You need special oceanographic winches with thousands of meters of electro-mechanical cable—Healy has 36,000 m—you need hydraulically operated cranes—she carries five, not counting the big A-frame on the transom—for the heavy-industry aspect of ocean science. Bottom-mapping sonar and acoustic current profilers built into the hull; INMARSAT systems for high-speed data transfer; and a half-dozen other high-tech unwieldy acronymic systems: you need them all, as well as multiple lab spaces, science conning stations, holds and freezers, and too many other things to list. “Yes, when I make whipped cream I like to marry it with the particular dessert,” said Dominic, one of the cooks about his pecan pie and coffee-flavored whipped cream. It’s not all science on Healy. There aren’t frills and filigree, but we live well; the cabins with adjoining heads are comfortable, and the food’s fine, three hots a day plus “mid rats,” that is, midnight rations. Science work goes on 24 hours every day, and of course all stations are constantly manned. Weekends are special. Burgers and fries for Saturday’s dinner and Bingo in the hanger. Brunch is served on Sundays.

She can carry a total complement of 125: 12 officers, 10 chief petty officers, 53 enlisted personnel, 35 scientists, and in a pinch, 15 others the CG calls “surge,” usually scientists. This is considered good duty, serving aboard Healy, but it’s hard on families at home. She entered the Arctic in May and won’t return to Seattle, her homeport, until October. (We’re the last science party of the season.) There she’ll be refitted aloft and alow; they’ll conduct fire-fighting, damage-control, small-boat and other drills during the winter, then next May she’ll return to the western Arctic and do it all over again. Precisely what she’ll do will depend on the science she’s asked to perform. Among the things you notice right after her size is her motion, or lack thereof. We haven’t had any heavy weather to interrupt science operations, 25 knots maximum, maybe some higher gusts. But that was enough to set up six-foot seas and enough to feel on smaller research ships we’ve known. Healy was impervious, hotel-like. I don’t want to jinx us, so I won’t go around saying this aloud, but I for one am curious about her motion in a seaway. Not to mention her icebreaking. There’s a fair chance we’ll see that later in the trip when we turn north. I hope.

She’s named for Capt. Michael “Hell Roaring Mike” Healy, one of ten children raised by his father, a Georgia plantation owner in the 1830s and Mary Elizabeth Smith, a former slave. While many of his siblings went into the clergy, Hell Roaring went to sea, as a cabin boy at twelve. Some people must be born nautically talented, Healy, for one, and he quickly rose to officer in merchant vessels, and in 1864 he applied for commission in the U.S Revenue Marine, forerunner of the Coast Guard. Twenty years later he took command of the cutter Bear. Mike and his ship soon attained legendary status in the Alaskan Arctic. It was a wild and lawless place in those days, and Capt. Healy served essentially as the U.S. governor of Alaska, enforcing the law, suppressing illegal trade and poaching, delivering supplies and medical attention to far-flung native villages. Also, Healy was among the pioneers of Arctic science and conservation. The great naturalist John Muir, who sailed on several expeditions with Mike and Bear, writes glowingly of the captain’s skill in the ice, his intrepidity and integrity. His namesake upholds a proud and little-known Coast Guard mission in the Arctic.

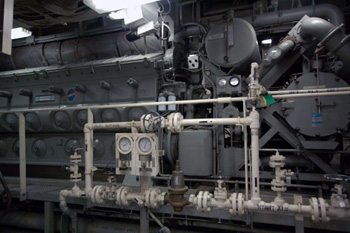

Here are some of Healy’s particulars, and then we’ll let the photos describe life aboard: Length: 420’ Maximum Beam (distance from side to side): 82’ Draft, loaded: 29’3” Propulsion: Four Diesel electric engines delivering 30,000 horsepower to the propeller shafts. Fuel Capacity: 1,220,915 gal. (She burns in normal operations about 12,000 gal. per day, more when breaking ice.) Speed: 17 knots Endurance: 16,000 nautical miles at 12.5 knots (By the way, one knot of speed equals 1.15 MPH.) Last updated: September 28, 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||