The Angry Irminger by Dallas Murphy

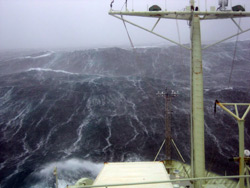

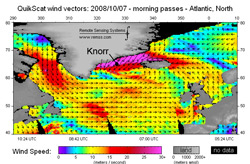

I wish you all could see what I’ve just witnessed from the bridge. Chief Scientist Bob and the captain are ribbing me, saying it’s my fault because I wrote to you yesterday that the storm wasn’t so bad. I jinxed us, they say. Maybe they’re right; I won’t do it again. This one is vicious. It’s been blowing steadily 50 knots for most of the day, and guys told me they saw gusts to 73 knots this morning. That’s hurricane velocity. The seas are astounding, frightening and beautiful in their violence. Waves are averaging easily 30 feet, many far larger, but raw numbers don’t do them justice, great rearing walls of water, breaking white on their crests, streaks of spume running down their faces, occasionally sweeping over the bow. The entire ship shudders when she buries her bow in the face of the waves. All work has ceased. “We have an ice berg at 3.8 miles,” said the Second Mate peering at the radar screen. We’re only 25 miles from the high East Greenland coast, but we can’t see any trace of it. Kyle, the bosun, came on the bridge to say that we’re taking water through a ventilator on the second deck. “Guess we’ll have to go out there and cover it,” he said. He and two other guys suited up and staggered out on the deck below the bridge with a plastic tarp. The wind shredded it as they tried to lash it over the ventilator. Tough, brave guys, they went below to get something stronger, and it took nearly 30 minutes to cover the opening, while icy spray lashed their faces. All in a day’s work in the Irminger on this fine ship, but even the experienced salts were impressed by these seas. Wait, not all work has stopped. Ben and the atmospheric scientists just tried to launch a weather balloon, technically called a radiosonde from the aft deck, but the wind ripped off the instruments. They want to better understand the structure of the atmosphere in this under-sampled region, particularly during storms. In fact, part of the reason we’re out here in October is that this is the beginning of storm season. Autumn and winter storms tend to track eastward over Newfoundland on past Cape Farewell and into the Irminger Sea. As we said yesterday, there is that relationship between air and ocean, and Dr. Bob is interested in determining the effect of storms on the ocean circulation in and around the Denmark Strait. The Danish Meteorological Institute, which has delivered spot-on accurate forecasts thus far, predicts that we’ll get brief relief from heavy weather tomorrow; if so, we’ll be treated to views of the magnificent Greenland coast. Dr. Bob is interested in measuring the East Greenland Current, which flows south from out of the High Arctic. Because of location and direction of flow, the East Greenland Current often brings ice down with it. That might prevent us from steaming as close to shore as Bob (and the rest of us) would like. Knorr is ice-strengthened, but she is not an icebreaker, and the captain will exercise extreme caution when ice is nearby. Speaking of Greenland and ice, this might the time to introduce the Greenland Ice Sheet into the climate mix. Greenland is by far the largest island on Earth, nearly the size of Western Europe. But only the thin coastal strip, about 15 percent, is habitable by people or animals. The rest is covered by this giant dome of ice twice the size of California soaring at its highest point to 10,000 feet. That’s a technical term, ice sheet, referring to a rare and particular kind of glacier. The difference between a glacier and a great chunk of frozen freshwater is movement, the downhill flow of ice. An ice sheet grows as annual snowfall accumulates and converts to ice under the press of increasing weight. (The ice at bedrock level in Greenland fell as snow 110,000 years ago!) But the ice sheet cannot grow indefinitely. At a certain point, the ice spreads and flows outward in tongues of ice that eventually reach the ocean where they break off in the form of icebergs. An iceberg from west Greenland sank the Titanic. Troubling changes are taking place on the ice sheet due to global warming. It’s not exactly accurate to say that the ice sheet is melting. But the outward flow of ice into the ocean has increased radically in the last ten years or so. In 2007 alone, the ice sheet lost enough ice to cover the United States twice. The problem is that the ice sheet is made of freshwater ice, while the ocean contains saltwater. Ocean circulation depends in part on salt (“salinity”). If the North Atlantic Ocean’s salinity is diluted by too much freshwater, then the circulation pattern will change, and that will cause climate change. To understand just what effect the freshwater from the ice cap and from the High Arctic is having on ocean circulation is an important part of this expedition—because of its potential to change our climate. This is a fairly complex question, but it’s vital to us all, and we’ll be talking about it a lot more as the trip goes on. But for now, please keep this in mind: Everything is connected in nature’s system—ocean, wind, ice—and you can’t change one without changing the whole. Ermingeri kamappoq by Nick MøllerUllut kingulliit tunup imartaani suliniarnerput killeqarpoq. Ullumi aquttarfimmut pulaarama umiarsuup ittuata kilerrippaanga anori 50 knob tikillugu sakkortussuseqartoq, taamaaseriarluni oqalunnini nangeqqiinnarlugu, ullaaq anorlerlualeruttormat 73 knob angusarlugu anerersuarsimasoq, oqaatigivaa. Anerersuaq taamak sakkortutigisoq uniorpallaassanngikkukku pitserartut sakkortussuseqarpoq. Mallit qaavisigut qaqortumik qapummik qalipaatinillutik, maliup nuuaniit ammut naqqanut 10 meter tikillugu portussuseqartarlutik, isigisaq pikkunaqaaq ersinapassittumik kusanartumik malissuit pallitassaanngitsutut isikkoqarput. Sila taamak kamassimaartigitillugu avataani suliaqarniarneq ajornakusooqaaq, umiarsuarmilu sulisut amerlanerit suliaqarnertik unitsikkallaqqavaat. Aquttarfimmi aquttuunerup radarikkut takutippaa sikorsuaq umiarsuarmiit 6.km isorartutigisumi issimasoq, tamakkuuppullu umiarsuarmi inuttat mianersuutassaat, umiarsuaq mattussagaagaluarluni sikusiutaanngilaq, taamaattumik sikorsuit qanillinaveersaarnissaat eqqumaariffigisassaavoq. Oqaluttuanimi naammattuugassaavoq sikorsuaq kalaallit nunaata sermersuaninngaannersoq atlantikukkut kujammut sarfarsiataarnikoq, umiarsuup “Titanic” aporlugu umiuffiginikuummagu. Radari atorlugu kalaallit nunaata kangia takusinnaavarput, umiarsuarmiit Tunup sineriassua 40.km isorartutigaaq, soorunalimi isorartussuseq taamak annertutigisoq nunataq takusinnaanngilarput. Ah usi sila taamaakkaluartoq silasiortugut ballon-imik qangattartitsipput, ballon atorlugu silaannaq paasiniarneqartarpoq qanoq isugutatsigineranik qutsinnerusumilu qanoq anorlertigineranik misissuisarlutik. Ullup ingerlanerani anorlerpallaanngikkaanga ballon-imik arlaleriarlutik qangataartitsisatput. Sermersuaq aakkiartornera nunani allani soqutigineqarnera piffissami kingullermi annertusiartortillugu oqartarneq “sermersuaq aakkiartortoq”, tamanna namminermi eqqoqissaanngilaq, tassami sermersuaq toqqaannartumik aakkiartunnginnami. Kisianniliuna sermeq iigartartoq silaannaap kissikkiartorneranik immallu kissakkiartorneranik, imartami aattarnera annertusiartortoq. Taamaasilluni ukiup kiatsiffiani sermersuarmiit kangerlutsigut sermeq anisartoq annertusiartortoq, imaanilu aattarnera sukkanerulersoq. Tamannaavorlu ilisimatuut soqutigilluinnagaat, immap tarajoqassusianut sunniuteqarataarnissa ilimanarluinnarmat, piffissami kingullermi silaannaq nunarsuatsinni mingutitsineq aallaavigalugu kiatsikkiartornera ersarissiartormat. Sermeq iminnguuttartoq imartami annertusiartortillugu oqareernittuut immap tarajoqassusianut allanngortitsissaguni, taava nunarsuarmi tamani silap pissusaa allanguuteqartussaavoq. Anorersuartarnera, siallertarnera kiassutsimut kalaallit nunaaniinnaanngitsoq nunarsuarli tamakkerlugu sunniuteqassalluni, paasiuminaassinnaagaluarpoq unali paasinarpoq: Nunarsuatsinnimi suna tamarmi ataqatigiippoq, sermiuguni – aneriuguni – imaq, immaq tarajoqassusia, arlaat ataaseq allanngorpat tamanut sunniuteqassaaq, ataasiinnaq allanngorsinnaanngilaq. Last updated: October 17, 2008 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||