In Eirik's Wake by Dallas Murphy

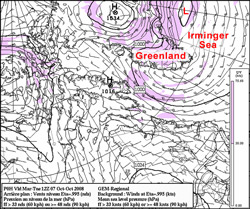

When it’s rough in the Denmark Strait, I think about the Vikings crossing this nasty body of water from Iceland in their open boats with their families, animals, and all the other stuff necessary to start a new life in Greenland. Eirik Thorvaldsson Raudi—Eirik the Red—was born about 950 on a farm in southwest Norway. Even by Viking standards, Eirik was a violent fellow. Still a teenager, he was implicated in “some killings,” as the sagas put it, and he was banished from Norway. He moved to Haukadal, on Breidafjord Fjord, Iceland. But Eirik just didn’t fit in. When he killed someone else, he was forced to move again, to Oxney, 50 miles away. Yep, it happened again, and this time Eirik was banished entirely from Iceland—for three whole years. He knew where he wanted to go, at least sort of. About 50 years earlier, one Gunnbjorn Ulf-Karkason, en route to Iceland from Norway, was blown far off course, and when the weather cleared, he sighted a forbidding coast of towering, icy mountains and vast glaciers. It didn’t look very attractive to Gunnbjorn, so he turned around for Iceland without landing. But like all sailors, he talked a lot, and told the story of this giant landmass in the west. Whatever that place was, it sounded to Eirik like the answer to his pagan prayers, and off he sailed, under the Snaefellsnes Peninsula (Iceland) and into open water. Four days later Eirik and his crew sighted sharp white mountains poking through the low cloud, and if, as historians claim, he sailed along the 65th parallel, then Knorr has been crossing and re-crossing Eirik’s wake. That coast must have appeared terrifying to cold, tired men in open wooden boats 130 feet shorter than Knorr, but these guys didn’t feel fear or fatigue like normal sailors. Eirik coasted south and probably sailed through Prinz Christian Sound to the gentler west coast, where he found a sweet fjord flanked by sloping grassy meadows with wildflowers—buttercups , angelica, harebell, and pink thyme—growing in profusion. He liked it, and modestly named it Eiriksfjord. There he would make his new home. When the three years were up, he sailed back to Iceland to recruit additional settlers to, well, where? He needed an alluring name, something nice that farmers might like. How about… Greenland? Yes, that had an attractive ring to it. The story of Vikings in Greenland is fascinating and troubling, but it’s not our story. Greenland, however, is definitely part of the story of our expedition. No fool, Eirik first sailed to Greenland in early summer. No mariner in his/her right mind goes to sea in search of storms. But as we said yesterday, neither Knorr nor her work is normal. And to experience storms, their effect both on the atmosphere and the ocean, is a prime part of Dr. Bob’s plans, and that’s partly why we’re out here in October during storm season. Today, let’s just introduce the factors involved in the interaction between storms, the Irminger Sea, and that giant island Eirik called Greenland, starting with storms: You might think of a storm as a hole in the atmosphere, called a low pressure area. (That’s why mariners, who measure air pressure with a barometer, grow alarmed when the barometer drops.) Nature doesn’t like holes in the atmosphere, and tries to fill them—with wind. On a stationary Earth, wind would blow straight downhill from regions of higher pressure toward the center of the low pressure in a wagon-wheel pattern. But Earth is not stationary. At the latitude of the Denmark Strait, Earth is hurtling eastward at 500 miles per hour and on the equator at 1,000 mph. We don’t notice the speed because we’re firmly attached by gravity to Earth, and our atmosphere is moving along at the same speed. But things less firmly attached, such as wind and water, are significantly affected by Earth’s rotation. One effect is to alter that wagon wheel pattern, bending the wind to the right (in the Northern Hemisphere). Therefore, the wind blows around the center of low pressure in a counterclockwise direction. The opposite is true in a high-pressure zone, but high pressure usually brings fair weather. The deeper the low, the stronger the wind. On a weather map, you’ll see a lot of concentric circles around the point of lowest pressure. These circles, called isobars, indicate areas of equal barometric pressure. If there are only a few isobars, then the low isn’t very low. On the other hand, if there are a lot of isobars tightly packed, that means that the hole in the air is very deep, and the wind will be very strong. We’ve been receiving weather maps aboard ship, and nearly every day they’ve shown a low situated southwest of Iceland. It’s not parked there. Instead, it represents another of a series of lows marching across the North Atlantic. Let’s stop there for today, since this is lot to absorb. We’ll talk tomorrow about the significance of the high plateau of Greenland and its impact on storms—and, later, the related impact on the ocean currents in this stormy region. Silaannaap allanngoriartornera by Nick M?llerUllut tamangajalluinnaasa tusartarparput silaannaap kiatsikkiartornera, sumulluunniit nunamut pigaluarutta kikkut tamarmik oqaluuserivaat, eqqarsaatigalugu sunamiuna taanna silaannaap kissatikkiartornera oqaluuseriinnaraat. Naatsumik oqaatigalugu, silaannaap kissatsikkiartorneranut peqqutaatinneqarpoq silaannaq CO2 nunarsuatta silaannaani annertuallaalersimasoq. Tamannalu pissutigalugu qinngornerit seqinermeersut nunarsuatinnut pisartut, nunarsuatinniillu silaannarsuarmut utersaartutut isillutik ingerlaqqittartut, nunarsuup silaannaa CO2 – mik akoqarpallaalersimanera pissutaalluni, qinngornerit silaannarsuarmut utertussaagaluit, nunarsuarmut utersaaqqittartut. Taamaasilluni kissaq ingerlaqqittussaagaluaq nunarsuatinni uningaannartarluni, qinngorillu kissarnerat nunarsuatsinni silaannaap kissassusia ukiuni kingullerni 5° celsius tikillugu kiannerusersissimava. Kiannerulernera kisitisitigut annertunngikkaluartoq ullumikkut takusinnaalersimavarput, pingaartumik Kalaallit nunaani sermersuaq inisartoq kangerlutigut annertunerulersimanera ilisimatuut arlerinartutut sukkassuseqanerarpaat. Sermeq nunarsuatinni annikilliartortillugu qinngornerit seqinermeersut, silaannarsuarmut utersaartartut annikinnerulissapput. Qinngornerimmi sermimut apummullu qinngoraangamik, qinngornermik utersaartitsisarnerat allaniit annertunerummat, assersuutigalugu qinngornerit imaanut narsaateqarfimmulluunniit pigaangamik, kissaq annertooq tigusarmassuk. Akerlianillu aput sermerlu kissamik tigusaqaratik annertuumilli qinngornermik utersaarttsisarmata, tassa sermeq nungukkiartortillugu kiatsikkiartorneq aamma sukaneruleriartussaaq. Ullumikkumummi sermeq Kalaallit nunatsinni ukiumut peertartoq annertuujuvoq, allallumi nunarsuatinni illoqarfiit unoqarnerpaartasa ilaat, New York ukiumut imeq atortagaa, sermip kaangartartup ullormut Kalaallit nunatsinni angullugu annertussuseqarluni. Sermersuit nunarsuatsinni annertuut nunani arlalinni naammattuugassaapput, qaqqarsuarni sermersuaqararpoq annertuunik, tamakkuupput silaannaap kissatsikkiartorneranik aamma milliartupiloortut. Taamatullu qalasersuup avannarliup ukioq kaajallallugu sikuusarnera silaannaap kissatsikkiartorneranik annikilliartornera ilisimatuut misissuinermikkut paasisimavaat. Tamakku tamarmik issittup nunaani uumasunut sunniuteqarput, piffissami kingullermi tusartuarparput nannut nungukkiartupiloortut, nannummi sikoq ilulissallu atorlugit avannaarsuaniit upernalernerani kujammut ingerlaartarput nerisassarsiorlutik. Sikut ilulissallu nungukkiartortillugit nannut kujavartersinnaanerat nerisassaqarniarlutik ajornarsiatuinnavissaaq, tamannalu nerisassaaleqinermik kinguneqartussaalluni. Tamanna assersuut annikitsuinnaavoq silaannaap kissakkiartorneranut sunniutaasut sunniuteqartussallu, siunissamimi silaannaap kissernerulernissa ilisimatuut qularnaatsumik ilimagiluinnarpaat. Ukiummi 20 – 30 – it qaangiuppata Kalaallit nunarput sermersuaqassanerpa ulluinnarni tamakkuupput eqqarsaatiginarsinnaasut, kisianni ilimanarneruvoq taamanikkussamut suli nunarput sermersuaqaumaartoq. Periarfissat suut pilersinneqarsinaalissappammi, tassami nunarput kiatsikiartortillugu narsaateqarsinnaanerit aammalu uumasuutearsinnaanerit ajornannginnerulissapput. Tamakkulu atorlugit inuutissarsiorneq ingerlanneqalissagaluarpat siunissaq ungasinnerusoq eqqarsaatigalugu, inuiaqatigiit nunalerinermik uumasuuteqarnermillu ilinniartinneqassapput. Tamannalu piffissamik annertuumik aningaasatigullu nalituumik kinguneqartussaavoq, silaannaq kianerusoq inuuniarnerlu periarfissagissaarnerusoq atugarilissagaluarutigit, kalaallit kulturerput piniartuuneq aalisartuuneq sumummi pissappat. Ilimagilluarsinnaavarput qulakkeerlugu, siunissami kalaallit nunaani inuuniarnertigut suliassat annertuut ingerlanneqartariaqassammata. Pingaaruteqarporlu nunatta allanngoriartornera malinnaaffigissallugu, allannguutillu naapertorlugit nalimmassartuarnissaq, taamaasiunngikkuttami eqqarsaatigiuminaapoq qanoq kinguneqarsinnaanersoq. Last updated: October 17, 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||