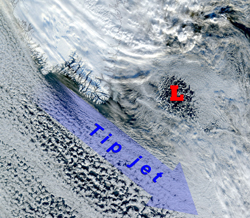

The Great Big Barrier by Dallas MurphyThe weather the last several days has been calm by Irminger Sea standards. The temperature is hanging around freezing, but it feels much colder, seeping perhaps into our bones. I probably shouldn’t say these words, but here goes: We haven’t had a storm in about a week. However, as we said yesterday, part of the purpose of being here in October is to measure the effects of storms on the ocean, the atmosphere, and the interaction between the two. If you’ll haul out your maps, we’ll have look at the storm tracks and add Greenland into the mix. Find Labrador and draw an imaginary line from there to Iceland. This is the approximate route of North Atlantic storms, beginning now. Notice that your line runs through the southern part of Greenland, shaped like a blunt wedge. This is not just any land standing in the way of storms. Greenland is enormously high, climbing, more precisely, soaring to 3,000 meters. There is almost no flat land on the Greenland coast. The mountains rear straight out of the ocean, and the interior ice sheet climbs even higher. Greenland forms a giant vertical wall standing so high that the storms cannot climb above it. When they slam into the wall, they are forced to change their course. The ocean, the weather, and climate are all affected by the fact that southern Greenland interferes with the track and behavior of winter storms. Let’s go back to Labrador and Newfoundland to follow a typical storm, bearing in mind that in the real world there is a lot of seasonal and annual variation in the direction, course, duration, and velocity of storms. Some are as powerful as hurricanes, but perhaps the average is similar to the storm we experienced early in the cruise, about 55 knots with gusts to hurricane speed (74 mph). Winter sets in. Some portion of the Labrador Sea, between Labrador and Greenland, freezes. Our storm heads east, picking up moisture—fuel—from the ocean, and the ice chills the stormy air. The low deepens, those isobars we described yesterday crowd together, and the wind blows hard, hard. The cold air not only churns up huge waves, it chills the upper waters of the Labrador Sea. Remember what happens then? Remember convection and that Count Rumford? The cold water sinks. Remember, we learned that nature insists that if a quantity of water flows north (as in the Gulf Stream), then an equal quantity must flow south. In order to flow south, in order to keep the circle unbroken, water must first sink. Part of the sinking “begins” so to say when our winter storm rages across the Labrador Sea. Then it slams into the high Greenland wall. Storms don’t like it when something big gets in their way; they get all frustrated and angry. When they hit the southern reaches of Greenland, they can’t get over it—so the winds whip around the southern point (Cape Farewell). Their velocity increases. By a lot. Then they careen into the Irminger Sea, and that’s one reason why the southern Irminger is on average the windiest spot on the entire world ocean. This tendency of storm winds to increase in speed when flowing around an impediment is called in technical language a tip jet. This, then, is the Greenland tip jet. But our storm is far from finished. Remember, as we said yesterday, that storms in our half of the world, circulate in a counterclockwise direction around the point of lowest pressure, or in technical language, cyclonically. Now our storm has reached the other side, the east side, of Greenland, and it’s a monster. The cold winds are blowing, say, sixty knots, and the thing covers hundreds of miles. The waves are huge; they drive the cold deep below the surface of the sea, just as they did in the Labrador Sea. Let’s “stop” the center of the storm for a closer look while it is situated 100 miles southeast of Iceland. It’s raining in Ireland and Scotland and Norway, and the winds are blowing umbrellas inside out. But the winds would not be as strong as in Iceland, because those countries are farther away from the center of the storm. Iceland would be getting high winds from the south to southeast, and maybe it’s snowing. (Do you ever get out of school for snow in Iceland?) Now let’s look at conditions west of Iceland in the vicinity of the Denmark Strait. If Greenland didn’t exist, the storm winds could be blowing from the east. But the high wall of Greenland does exist, standing there as a wall of vertical mountains. And again the winds crash into it, and again the storm grows frustrated, angry. Since the winds can’t climb over the wall, they can only flow south along the barrier. The storm’s anger takes the form of increased velocity. It rages down the coast almost all the way back to Cape Farewell. In technical language, this is called a barrier wind. So to put it simply, Greenland’s presence changes everything. It changes the direction of storm winds. And by doing so it changes the way the ocean behaves. It causes sinking in both the Irminger and Labrador Seas by chilling the water. Later, we’ll talk more about Greenland and its far-flung influence on the ocean, the weather, and, finally, on our climate—and about exactly what Dr. Bob is trying to learn from his ocean measurements. We’ve noticed from your questions that you’re interested in the details of life aboard Knorr in these cold, rough seas. So let’s talk about that tomorrow. Ilisimatuutut aqqutit by Nick MøllerSila nillernani atoruminartorsuuvoq kiassiut 2 - 4° tikillugu kiassuseqarluni, silaannaap isugutassusia nunamilluni annertuginarsinaasoq avataani naliginnaasuuvoq. Silaannaammi isugutassusia kiassuseq apeqqutaalluni sialunnguuttarpoq imaluunniit silaannarmi isugutattut akulerusimasarluni. Ilisimatuut misissuinerminni CTD atorlugu imaani misissuijuarsinnarput, ullormut arlaleriarlutik imaanut aqqartittarpaat kilometer – llu affaa tikillugu ititigisumut aqqartittarlugu. Ilisimatuut taamatut angalagaangamik naliginnaasuuvoq sivisuumik illoqarfik qimallugu angalasarneq, apeqqutaalluni suna ilisimasassarsiorfigineqarnersoq aammalu suna siunertaanersoq, paasissutissat katersorneqarnerat allanngorarsinnaasarput. Amerlasuutigut ilisimatuut nunalerinermik, silasiornermik imartamilluuniit soqutigisaqartuni paasissutissanik katersineq pinngitsoorneqarsinnaaneq ajorpoq. Nunarsuarpummi ilinniarfigissallugu paasisassarsiorfigissalluguluunniit, nunarsuup suanikkaluarpalluunniit pisariaqartarpoq misissuiffissaq tikillugu ilisimasassarsiorfiginissa. Paasisammi katersukkat aallaavigalugit ilisimatuutut sulineq aatsaat ingerlalersarpoq, paasisat katersorneqareeraangamik suliarineqartarput, pisariaqartitat immikkoortiterneqarlutik, paasinarsarlugillu takussitissianngortittarlugit. Ilisimatuutut sulissagaanni sunamiuna ilinniagaq oqaatillu suut pisariaqartut. Tamakku pillugit paasisaqarusullunga ”Doktor Thomas” ilinniartorlu ”Kjetil” Ukioq ataaseq qaangiuppat doktorgrad-imut naammassisussaq apeqqarissaarfigaakka. Tupaallannanngitsumik tamarmik assigiipaluttumik ilinniarnertik ingerlassimavaat, eqqaalaassavaralu Thomas Tyskland-mi inunngortuummat ullumikkullu Schweiz – mi ilinniarfissuarmi atorfeqarluni. Kjetil, Wood hole oceanographic institution (WHOI) aammalu Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) ilinniartuulluni, qallunaatut taajuuteqartumik “fysisk oceanografisk uddannelse” toqqammavittut ilinniagaralugu. Marluullutik ilisimasaasarsiortut ittuat Bob Pickart naalakkatut angalaqatigivaat, taassumallu paaserusutai ilisimasassarsiorfiilu aallaavigalugit suliaqartarlutik. Thomas aamma Kjetil, meeqqat atuarfia naammassigamikku toqqaannartumik ilinniarnertuunngorniarfimmut ingerlaqqissimapput, ukiullu pingasut qaangiummata ilinniarnertuutut nasartaaramik ilinniarfissuarmut qinnuteqarput, soorunalimi tamarmik nunami allamiikkamik ilinniarfissuit assigiinngitsut pineqarput. (ilinniarfissuaq, Universitet) Nunanimi allani ilinniarfissuit qinigassaqarnerulluarput, pingaartumik pinngortitalerinerup tungaasigut kisissaanngiusartunik qinigassaateqartarlutik. Ajoraluartumik nunatsinni tamakku nassaassaanngillat, allaffissornerujussuummi tungaasugut ilinniarfissat nunatsinni qinigassat periarfissatuapajaajunerummata ilinniarfissuarmi tiguneqarsinnaasut. Amerika-mi Canada-milu ilinniarfissuit Europa-miit allaanerupput, Europa-mimi ilinniarfissuarni atuassagaanni ”kandidat” naliginnaasumik ukiut tallimat atorlugit anguneqartarmat. Amerika-kunnili ukiut siulliit sisamat atorlugit ”bachelor” anguneqartarpoq, ukiunillu tallimanik ilinniarneq ingerlateqqillugu angusiffigigaanni doktorgrad anguneartarluni. Tassa imaappoq ukiut qulinngiluat atuagarsornikkut pinngotitamilu misileraasarnertigut ilinniarfiuvoq, naammassigaannilu atorfik qaffasissoq anguneqartarpoq. Taamatut atuarnssami pingaaruteqarpoq pisariaqarlunilu, tuluttut oqalussinnaanissaq allassinnaanissarlu paasinarluinnartumik, taamatuttaaq kisitineq pikkoriffiginissa pingaaruteqarpoq. Soorunalimi piumagaanni tamakkua anguneqarsinnaapput, pingaaruteqarporli atuarfigisami pitsaasumik ilikkagaqarfiusumillu atuartitaanissaq. Atuassagaanni pinngortitalerinermut, aningaasaqarnermut, sanaartugassanik pilersaarusiortutut allatulluunniit qaffasissumut, qallunaatut oqalussinnaaneq allassinnaanerlu pisariaqarput. Atuartitaanerullu ingerlanerani atuakkat amerlanerpaartai tuluttut allassimasarput, tamaattumik tuluttut oqaatit atuarnerup ingerlanerani aammalu naammassilernerani pingaarnertut inissisimalertarput. Taamatut eqqaatsiarpakka siunissami periarfissassi ilaat, angorusukkussiullu pisinnaasasi. Kiammi ilisavavaa aqagu ulloq qanoq pisoqarmaarnersoq, immaqa siunissami arlarsi imartatsinni ilisimasassarsiorluni angalasalerumaarpoq.

Last updated: October 20, 2008 | |||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||