Alex KainSeptember 21, 2009This morning's rough seas prevented the Louis from refueling, a process that requires an entire day and the pumping of two-million liters of fuel from barge to ship. Rather than idly wait for the swells to subside, Chief Scientist Sarah Zimmermann decided to travel farther north for rosette deployments and to return tomorrow to the fueling site. The downtime today allowed scientists to begin analyzing samples that have been obtained during the first days of the expedition. One of those scientists is Kelly Young, a seagoing technician from the Institute of Ocean Sciences (IOS) in Victoria, British Columbia. Kelly's zooplankton research is unique on board the Louis--among an array of physical and chemical projects, it's the only biological field work that's being done. In an interview, Kelly explained the importance of gathering biological samples from the Beaufort Sea and how zooplankton help explain the movement of Arctic waters.

Why is it important to study Arctic zooplankton? Zooplankton are one trophic level away from the bottom of the food chain. They link larger marine species to the ocean's most fundamental source of energy, phytoplankton. Zooplankton distributions help map the ocean's biological productivity--a high zooplankton concentration is required to sustain biodiversity in a given area. Zooplankton are drifters and they need to exist in areas with stable currents that won't sweep them into regions where they won't survive. They're subject to the whims of ocean currents and other environmental conditions. For example, during El Niño years, zooplankton typically found off the coast of California end up drifting in a warm current to the coast of Vancouver Island. How are the biological samples obtained? We collect samples in giant mesh sieves called bongo nets, which we tow vertically to the deck of the ship from a specified depth. The nets funnel the zooplankton into storage units called cod ends, a term taken from the fishing industry. We then disconnect the cod ends from the nets and transfer the samples into glass jars. We usually sample 100 meters from the surface because we're interested in upper-layer productivity in the water. There's lots going on below that depth, so occasionally we'll do up to 1000 meters, but that takes a long time to deploy and reel in. How do you calculate zooplankton distributions from your bongo data? We have flow meters on the tops of all the nets, which measure the volume of water going through all the nets. From this data we can determine plankton distributions in our sample areas.

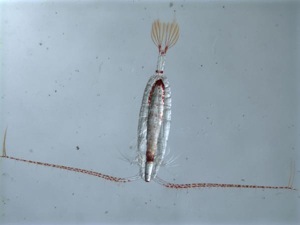

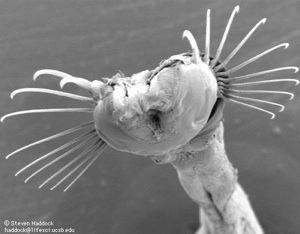

What sort of research will be performed on these samples? All the samples and data we obtain go to IOS scientists for genetic, oceanographic, and physical studies. Zooplankton samples preserved in ethanol will be used for DNA analysis to identify species and chart zooplankton distribution throughout the ocean. Formalin, a solvent that preserves zooplankton anatomy, is used to store taxonomic samples. All this research looks at the mixing of the world's water masses to understand how, when, and why they move. What zooplankton species have been recovered during this expedition? You can obtain up to forty unique species in one bongo net deployment. The majority that you see, though, are copepods, red-looking things with long antennae. We also get chaetognaths, commonly called arrow worms, but jokingly called Tigers of the Sea because they eat everything. If you see a close-up picture of the worm's head, it's got these huge, fan-shaped spines. When anything gets near it, the worm shoots forward and swallows it whole. There's also a common Arctic jelly species called a Aglantha digitale. You find them ubiquitously throughout the Arctic. We also get larvaceans, a type of urochordate. They have the beginnings of something that resembles a spinal cord, called a notochord.

We get mollusks in the form of pteropods, such as sea butterflies (with shells) and sea angels (without shells). Both have cool, jelly-like, transparent bodies and wings that they use to fly around the water. The sea angels completely depend on the shelled pteropods for a food source. The two are pretty tightly linked--where you find one you find the other.

All text and photos property of Alex Kain unless otherwise indicated. Last updated: October 7, 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||