Dispatch 27: Arctic Profiles #3 |

| |

Alex KainOctober 13, 2009

The following profiles compose the third of a three-part series that aims to explore diversity among the participants involved with the 2009 Joint Ocean Ice Study.

Name

Hugh Maclean

Affiliation

Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Institute of Ocean Sciences (DFO-IOS)

Hometown

Sidney, BC

What are your responsibilities on board?

I do a little bit of everything, but I work primarily as a watch leader and a sampler by monitoring rosette and Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler casts. I've been doing this now for 28 years.

What is your academic background?

I studied mining engineering at the University of British Columbia (UBC). When college ended, I met an oceanographer who was looking for someone with a geophysical background, and at the time I thought, "I'll be the first underwater miner!" After that, I did a lot of oceanographic contract work with UBC and other mining companies. After going to sea, I never looked back. I was born and raised in Vancouver and I can't be away from the water.

You studied mining engineering. Does this mean you worked in mines?

Sure. Out of high school I started working as a motorcycle messenger for a big mining company. My connections with the company provided me summer jobs throughout my time in university, mostly in diamond drilling, or drilling with diamond-impregnated blades. The jobs paid really well and I never had to take out student loans. Working one summer was enough to sustain two years of university, and buy motorcycles.

What were some of your living situations like at the mines?

I lived in a tent for a summer in the Canadian Rockies, where we heard grizzly bears every night. The camp was separate from the mine, so every day we had to sling oil and gas half a mile up this huge hill. When we didn't tie up the oil and gas at out campsite, bears would puncture cans and drink oil and gas.

What exactly did you do in these mines?

I worked mostly as a survey engineer, meaning I measured how much material was being removed from mine and determined where to continue drilling based on mineral characteristics.

Was that a dangerous environment?

Of course. We used to jump over mill holes 600 feet deep. You're always aware of the danger—it makes the job interesting and exciting. A ship is dangerous, too. It's slippery, icy. The hard hat I use now is the one from my mining days. If you take the right precautions you'll never get hurt. Never maybe not the right word, but it's essential to be careful, both underground and at sea.

Do you miss mining?

Sure. Just like oceanography, mining brings together an elite and special group of people. When I meet mining guys, we immediately get along and have lots to talk about.

Was it difficult to transition from mining to oceanography?

Not really. Most people think of mining as prospectors, pickaxes, headlamps, and dead canaries, but it's a sophisticated science that requires a lot of complex equipment, electronics, and sensors. Oceanography is much the same.

What is people's greatest misconception about the Arctic?

People think it's always minus 50 up here, but in summer it's quite nice. I remember last year it was 32°C (89.6°F) up here and all the Inuit kids were swimming. The ship, however, didn't have AC and the on board temperature hovered around 40°C (104°F). The ship's all made of steel so it was like living inside an oven. It was so hot you couldn't sleep.

Describe the Arctic in a few words.

White. Colorless. Lonesome. When you look out you see nothing. It's just so bleak. Beautiful and bleak. I know I'd be fine if I got lost in the woods, but I can't imagine being one of the early Arctic explorers; up here, I'd die in a night.

What's the first thing you will do when you get home from this expedition?

I'm looking forward to starfishing in my bed rather than lying in a tiny bunk and starting a roaring fire in my fireplace. For me, a roaring fire is like comfort food.

When you're at sea, what do you miss about home?

Family, friends, driving my motorcycle and truck in wide, open spaces, going 20 miles away instead of 20 feet. Anyone who's been to sea knows that every ship gets a little bit smaller every day.

I often fish and camp after I finish long trips. On Saturday, I'm actually going to Saskatoon, to go duck hunting. I spend about 6-7 months per year at sea, more than most Coast Guard guys, so when I go home I like to go into the woods and away from the ocean.

When you're back home, what do you miss about the sea?

The smell of salt air, my shipboard friends, not having to cook for myself. Since I've been doing this for so long, I know the whole crew aboard the Louis. I miss the camaraderie. We're a good group. We get along and get our jobs done.

Describe what it is like to feel truly cold.

It hurts. It's tiring. You shift into survival mode.

Describe the sensation of ice crunching under the hull of the ship.

Watching ice breaking is like watching a fireplace. You can watch it forever. If it weren't so cold I'd stay out there all day. It's mesmerizing. The sound depends on the quality of ice. Sometimes it's constant sloshing. Other times, it sounds like a dump truck unloading huge boulders into a metal dumpster.

Why is it so important to study the Arctic?

Because it hasn't been studied well enough before. This is a difficult and expensive place to access, but knowing about the Arctic is so important because it contributes so strongly to the stability of the earth's climate. It's the start of the entire world's weather system. The world circulation conveyer, a huge ocean system that controls climate, runs through the Arctic and it's not entirely understood how changes in the Arctic atmosphere will affect its path. It sends salty, cold, dense water sinking outside Greenland. It takes 500 years for water to be circulated entirely. It drives the weather for the whole world. If the Arctic were to melt, then you wouldn't have that dense sinking seawater, which could in theory cut off Gulf Stream to England. England would then freeze.

* * * * *

Name

Rose Ette

Position

Water sampler, CTD womb

Hometown

Handcrafted in Victoria, BC

Affiliation

Fisheries and Oceans Canada - Institute of Ocean Sciences (DFO - IOS)

Material composition

I'm made of sugar, spice, and tempered reinforced aluminum.

Duties

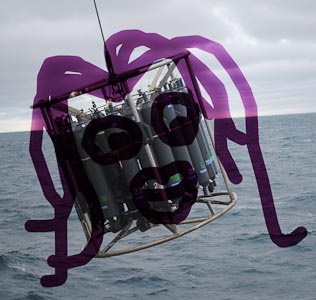

I plunge through the ocean and gather water samples and specified depths, all while nursing my beloved friend, the CTD.

Tell us about your love life, Ms. Ette.

Oh, baby, don't get me started. After my second year of studying geophysics and oceanography at the University of British Columbia, I dropped out live with my boyfriend, Earl, with whom I was completely in love. I thought we were going to spend the rest of our lives together. He promised me a family, eternal care, and a white picket fence.

Earl turned out to be neglectful brute who never took care of me. He refused to oil my joints. I was rusty for half the year. He didn't even clean my Niskin bottles. They coated with algae, which was terrible for my career as a cocktail waitress. When I first started serving drinks out of college, I was the hottest bartender in all of Victoria. I could pour 24 drinks at once, all with different salinities. They called me the "Double Dozen Doozy." But then, once I got covered an algae, no one would drink my cocktails. It was terrible. I'd pour a drink and it would be filled with tiny green specks of aquatic plant life.

I needed someone who could treat me better; I needed a man. But it was terrible. I was broke, I had no place to live, and all my bottles were coated in green sludge.

That's awful. How did you recover?

One day I was standing on a street corner in Victoria, begging for toonies by singing Joan Baez songs. At that time I was a mess—totally rusty, green with algae, barely able to pour a drink.

But then, I saw Mike Dempsey, my Mikey, as he was walking down the street with his adorable beard and smirk. Mikey saw me for who I really was; a sophisticated piece of oceanographic equipment, not a rusty, algae-covered, useless hunk of metal.

Mikey came to me and whispered, "Come, let's take you home." He brought me to the Institute of Ocean Sciences, where, for the first time since college, I felt like I could be myself. I didn't have to smile and make conversation with barflies or mix drinks seven nights a week just to get by. I could just rest and collect water samples when they needed me to. Since then, I've been in love with Mikey and the Institute of Ocean Sciences.

Describe the Arctic in a few words.

Slippery. Wet. Where I belong.

When you're at sea, what do you miss about home?

Junkyard Wars on the Discovery Channel

When you're at home, what do you miss about the sea?

Being so necessary to a group of people.

What's the first thing you do when you get home from a trip?

I rest, read a good romance novel, and make a water scrapbook of my adventures. The scrapbook has water samples from all over the world: the Beaufort Sea, the Persian Gulf, Antarctica. Each one reminds me of how happy I am with my new life in the water, with IOS, and with Mikey.

All text and photos property of Alex Kain.

Last updated: October 7, 2019 |