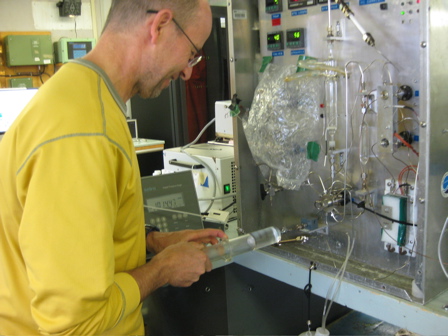

Gerty WardJuly 25, 2008Ocean water is like a sandwich. It is stratified-- full of horizontal layers some of which do, and others which do not, mix well with the layers near-by. These layers are determined by the density of the water. The primary factors affecting ocean water density are its salinity (how much salt is in the water) and temperature. However, in the Arctic the water temperature is fairly constant at just above freezing, so water density is determined primarily by salinity. The biggest sources of fresh water are rivers, rain and snow, and ice melting. Scientists sample water at specific depths, which represent these different layers, then measure a variety of factors in each sample. In this way, scientists "cut through the sandwich" exposing each layer, making a vertical picture of the ocean. The more factors tested, the more detailed and informative this picture is. We collect a lot of water. What is done with all this H2O? Here are a few of the processes. Rick Nelson and Nes Sutherland test the water for chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Although CFCs are no longer used on the North American continent, their progress through the Earth's water system is still being tracked. Monitoring where the CFCs flow is a good marker for where ocean waters flow. Linda White measured the nutrient content of the water. Just like you might test your garden soil for NPK, nitrogen, phosphate and potassium, Linda tests the water for NPS, nitrates, phosphates and silicates (a critical nutrient for ocean life). Scientists use nutrient signatures to identify the source of water.

Melissa Hennekes measures ammonium, another water source marker. Ammonium is an especially good "winter water marker" because as ice forms the salt in the water is left behind, making the surface water saltier and thus more dense. This more dense water sinks, and can be identified as a specific water layer, especially along the continental shelf.

Hugh Maclean measures the oxygen content of water. Remember: cold water holds more dissolved gas than warm water, so these Arctic waters can have a lot of oxygen! Of course, oxygen is necessary for life so low amounts indicate not many living things. This oxygen gets into ocean water primarily by the water interacting with the air at the surface. Ice floating on the water blocks this interaction. Thus the oxygen concentration can tell you about how much a specific layer interacted with the surface or how much life that layer can support. Chad Cuss measures the amount of organic matter -- the dissolved "detritus" -- in the layers. Knowing how much of this material is available for biological and physical processes at each layer of the "sandwich" helps to complete the ocean current picture.

Collecting this water is a 24/7 operation. When we get to the location of interest, the scientists go to work. Of course, being in the Arctic in summer means there is always light; still, it is a bit surreal. It is also hard, cold work. To get an idea of what water sampling is like, get a bowl of ice water and the parts to a small plastic such as a Lego guy, the more small parts the better. The water temperature should be just above freezing, about 2 degrees C. Put lab gloves on your hands (so that you don't contaminate the water). These gloves act in a mysterious "cold amplification" way. I am not sure how that works....Now put your hands into the water and start to build the Lego guy. This is water sampling: manipulating plastic parts in cold, cold water.

On another interesting note:

The dirt in the ice is from shore, brought on to the ice by wind and erosion. The sun is out, so I leave you with warm thoughts! All photos by PolarTREC teacher Gerty Ward unless indicated. Last updated: October 7, 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||