Please note: You are viewing

the unstyled version of this website. Either your browser does not support CSS

(cascading style sheets) or it has been disabled. Skip

navigation.

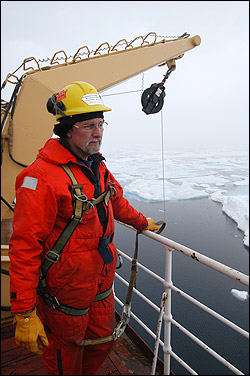

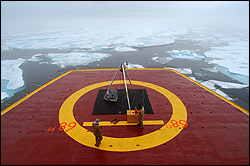

Chris LinderAugust 7, 2005

As we travel deeper into the Beaufort Gyre, the ice has become both more concentrated and thicker. The occasional ice-breaking rumbles of yesterday have been replaced by a steady (but totally devoid of rhythm) bass drum beat. While the ice certainly hampers our science operations (except for the ice buoy deployments of course!), it is undeniably hypnotic to watch. One of the most beautiful features of this otherworldly landscape is the melt pond. Melt ponds are shallow depressions of melted snow and ice that form in summer on the tops of large floes. The clear water reveals the blue ice below--a color blue that is so intense I like to call it "electric blue." A large field of melt ponds resembles a giant patchwork quilt or a jigsaw puzzle. Sometimes a pond will also have "melt rivers" running out of them, meandering like blue snakes across the pure white surface of the floe. Some of the ponds are tiny, the size of small kiddie pools, others like huge Olympic pools. None of them, however, are particularly deep--perhaps only a few feet at most. The CTD team spent some time today puzzling over "spikey" data (highs and lows that are way out of the normal range). They eventually identified the problem as a leaky connector and quickly replaced the damaged unit with a spare. Sarah Zimmermann is cautiously optimistic that their problems are solved for the time being "the data seems to be coming in ok.." The thickening ice is making other headaches for the watchstanders. Since we are progressing into deeper water (2,600 meters was the last cast I watched today), CTDs are taking nearly an hour and a half to make it all the way to the bottom and back to the surface. During that time, of course, the ice is shifting around the ship, and in some cases, snagging the CTD line. Using a combination of shiphandling skills and the bubblers, the crew managed to free the line every time. With no spare CTD rosette on board, we don't like to think about the alternative. Tomorrow if we make good time through the ice we could locate the buoy that stopped transmitting on August 1st. John Kemp and Kris Newhall have their recovery equipment set up and ready to go. We have a rough idea where to start looking--now we are just hoping it hasn't stopped transmitting because it has fallen through the ice floe to the watery depths. Last updated: October 7, 2019 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||