Please note: You are viewing

the unstyled version of this website. Either your browser does not support CSS

(cascading style sheets) or it has been disabled. Skip

navigation.

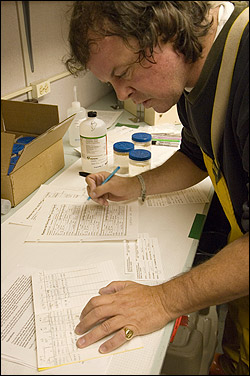

Chris LinderAugust 12, 2005A deep baritone rumble woke me from my sleep at about 6AM this morning. I knew immediately what it was, though, and what it meant. After nearly two weeks aboard the Louis, you become accustomed to the sights, smells, and sounds of the ship. This particular rumbling comes from the bubbler system, and it indicated that we were at a science station. The bridge uses blasts of compressed air from the bubbler to keep ice away from the instruments while they are in the water. When it's busy blasting ice away, it sounds like a cross between a 747 jet engine and a runaway train. Since I was awake, I decided to investigate. One step on deck and I wished I had stayed in bed. A howling wind whipped mist in my face and coated my lens with a damp spray that I couldn't wipe off. Hugh Maclean, Jeffrey Carpenter, and Will Burt were braving the foul weather to collect some critters with an instrument called the bongo net. At roughly 15 feet in length, the bongo is actually four separate net openings attached to a wire frame. The nets are lowered down to 100 meters depth, and then raised back to the surface. Any creatures that are caught in the nets get rinsed down into collection jars at the ends of the nets. On deck, it looked like they had caught, well, some goo. Back in the lab, however, when the goo was transferred to clear glass jars, we could see that it was actually full of tiny creatures. "Looks like we've got both phytoplankton (marine plants) and zooplankton (animals). The feisty swimmers are copepods, one of the most important parts of the Arctic Ocean's food chain" Hugh explained. Hugh then preserved the samples and boxed them up for analysis after the cruise. This data will be combined with the our other measurements to help understand the Arctic system as a whole. After breakfast the mooring crew launched into action. Starting with a 3,800 pound anchor (the weight of two mid-size cars), the mooring was carefully lowered over the side piece by piece. Throughout the long, grueling day, over ten people helped with the mooring deployment, from attaching instruments to operating the cranes and winches. Like an orchestra conductor, John Kemp directed the operation with hand signals and his distinctive whistle. Five and a half hours later, only the orange top float was visible. One sharp tug from the quick release and it sank out of sight beneath the waves. The instruments are already collecting data for us--we'll see next year what they have recorded. One Beaufort Gyre Observing System mooring down--now it's off to the Mooring B site, roughly 180 miles to the north. Along the way we will be stopping for regularly spaced science stations, sampling day and night with CTD and XCTDs. Last updated: October 7, 2019 | |||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||